How long can the coronavirus survive on surfaces?

Several studies have attempted to estimate how long the COVID-19 virus remained infectious on inert surfaces, but the figures are more complex to understand than they first appear.

This is possible, based on studies that have attempted to determine the duration of "survival" of Sars CoV-2 on inanimate surfaces.

But even if the risk exists, these durations should not be taken literally and should be put into perspective with the way researchers are trying to measure them.

How long can the virus survive on surfaces and objects?

It should be made clear at the outset that it is inappropriate to speak of the "survival" of the virus since the virus is not really "alive"."Rather, we are talking about maintaining infectivity, how long it remains infectious," says Astrid Vabret, head of the virology department at Caen University Hospital and coronavirus specialist.

The stability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (responsible for Covid-19 disease) depends on the type of surface considered, according to the two main scientific studies published to date on the subject.

The first, published on February 6 in the Journal of Hospital Infection, tested the virus on eight different surfaces and compared it to other coronaviruses (such as those responsible for SARS 2003 or MERS 2012).

Researchers have found viable strains of the virus up to five days after spraying steel, glass, or ceramics

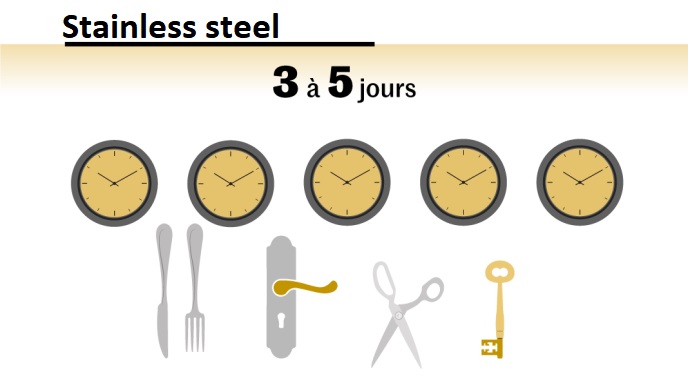

Results show that the virus can persist on these surfaces for between two hours and six days (less if the ambient temperature approaches 30°C).Researchers found viable strains of the virus up to five days after spraying steel, glass or ceramics, without being able to measure how much was found on each of these surfaces.

The results were quite variable (two to six days) for plastic, while on latex and aluminum, a few hours were sufficient to kill all strains.

A second study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 17, tested the resistance of the virus on other materials, such as cardboard and copper, or in the air by aerosol spraying.

The results show shorter persistence times than those published in previous studies, ranging from three hours (aerosols) to a maximum of three days (steel, plastic), with intermediate values (twenty-four hours for cardboard) for the same amount of virus sprayed.

But the two studies agree on one point: plastic and steel are the surfaces where the virus has been stable for the longest time.

A third publication, from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recently reported that the genetic material of the virus had been detected in the infected passenger cabins of the Diamond-Princess ship, where 3,700 people were quarantined in February until 17 days after they left.

But it is not possible to infer that transmission from these contaminated surfaces occurred, the authors of the study said, calling for further investigation.

As the material conditions (e.g. temperature, humidity) are not known, it is relatively difficult to assess the validity of such a duration, and any conclusion would be imprudent and hasty at best, or at worst totally false.

"We can't even be sure that the virus we find can reinfect. It's far too vague," says Bruno Grandbastien, medical officer of health and president of the French Society of Hospital Hygiene.

"You mustn't cling to a specific number, because it doesn't correspond to anything in life."

What, then, should we think of the durations evoked in these two studies? These studies are important to give an idea, an order of magnitude of the time during which the virus remains infectious," replies Astrid Vabret.

We shouldn't cling to a precise figure, because it doesn't correspond to anything in the living world.

The interest of these studies is that the way of counting is the same throughout the duration of the experiment, the comparison between two surfaces remains valid. »

"The doses are rather representative of a real situation since it is estimated that this order of magnitude will be found in nasal swabs," says Dr. Grandbastien.

But the doctor points out that the duration of persistence in aerosols is probably longer than in reality. "We don't find aerosols as fine as that in reality, because this virus is transmitted via large droplets which, by gravity, will fall back more quickly. »

In summary, depending on the surface, the SARS-CoV-2 virus can persist for approximately :

What are the risks of contamination?

This is the central question, but it is also a question that is very difficult to answer. In their study, the researchers make it clear that the transmissibility of the virus to people who come into contact with infected surfaces has not been demonstrated due to a lack of data."The real problem is that we don't know the infective dose."

The real problem is that we don't know the infecting dose," says virologist Astrid Vabret, "which is the amount of virus sufficient to generate an infection.

But this changes the way you interpret how long the virus persists: if the infecting dose is low, it would mean that a surface remains infectious for much longer than if the infecting dose is high.

"The transmission of a virus is a complex phenomenon that is very difficult to quantify. We don't know how many viruses it takes to generate an infection in contact with the mucous membrane.

It's probably not the same for different people. You have an enormous diversity of everything: local defenses vary depending on the individual, as does the state of their mucous membranes. »

A point confirmed by Bruno Grandbastien. "We have zero data on this, we just know that there is a gradient: the higher the viral load, the greater the risk of infection. But it's highly variable depending on the virus. »

Do we have to clean all the products we touch?

This is a question many people ask themselves after receiving WhatsApp or Facebook messages recommending to "leave groceries in your car for 1.5 hours" and then "pass everything that may have been touched by others with diluted bleach".This recommendation is anxiety-provoking and excessive, according to Professor Vabret: "If you wash your hands regularly, and don't put them to your mouth, you eliminate what you could have picked up. »

"We are not in a situation where we are asked to disinfect the food we eat, there is no risk of becoming infected through ingestion".

This information is not at all scientifically supported," says Bruno Grandbastien. We are not in a situation where we are asked to disinfect the food we eat, there is no risk of becoming infected through ingestion.

On the other hand, we can recommend washing both the products we have touched and our hands, which are basic hygiene rules that should be applied outside of any epidemic. »

Leaving your shopping for an hour and a half in the car is therefore useless given the persistence of the virus on cardboard and plastic surfaces: it is above all recommended to wash your hands after shopping, as they are the main vector of transmission.

Cleaning or even disinfecting work surfaces that we often come into contact with do not seem unreasonable either.

For the most worried, even if the risk is "absolutely minimal" according to Anne Goffard, a virologist at the Lille University Hospital, interviewed by France Culture, cleaning cardboard or plastic packaging brought in from outside contributes theoretically to further minimize the risk; remembering all the same that the capacity of the virus present on surfaces to infect the organism has not been established at all.

As for textiles, there is no scientific data on the ability of the virus to resist it. The virus is easily destroyed at temperatures as low as 30°C, according to Dr. Georgine Nanos, interviewed by HuffPost. It is, therefore, unnecessary to opt for washing programs at 60°C.

Comments

Post a Comment